Our last essay detailed the connect and manage philosophy behind Texas’s energy success. This essay explains a technicality–other states claim to have a Texas-like system. Yet Texas’s process is months faster. Why?

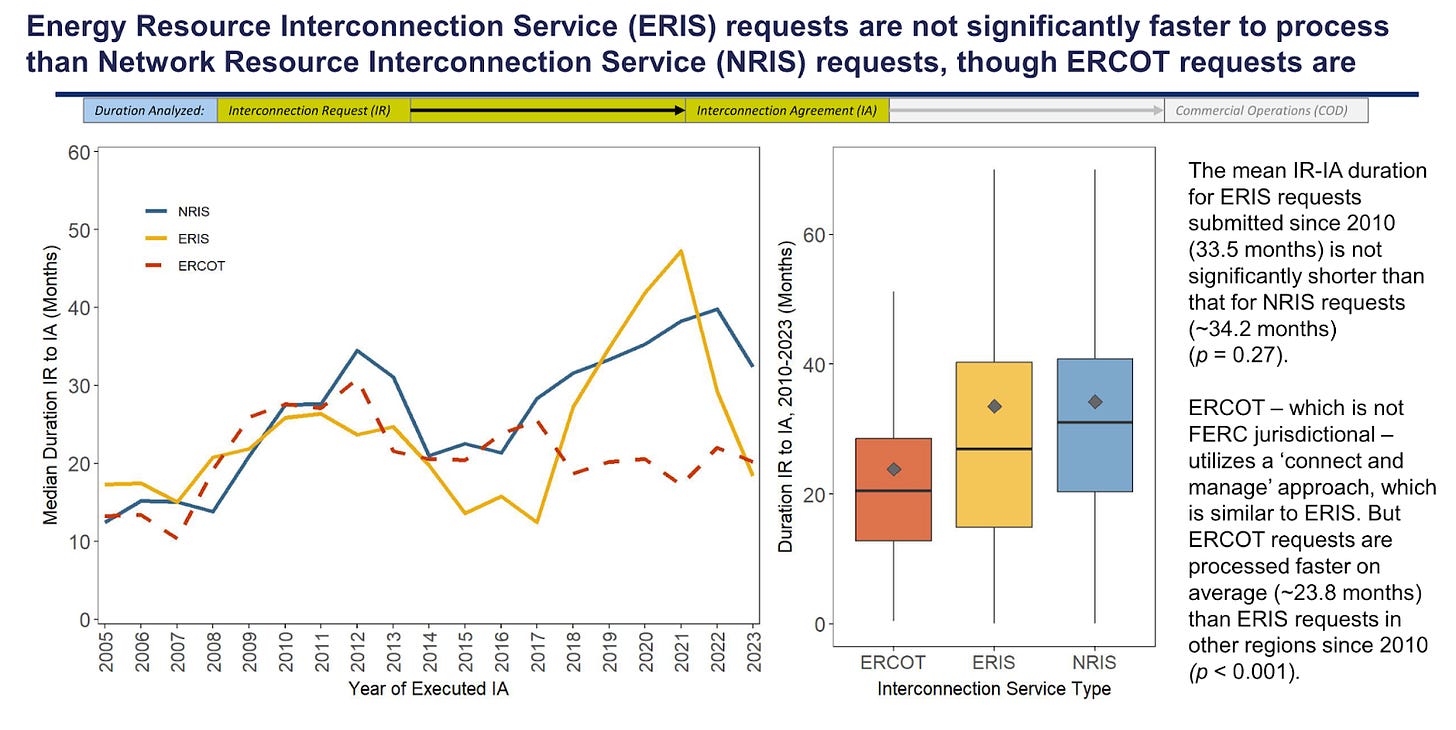

This graphic from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory’s 2024 Queued Up report explains how Texas is doing something no one else can.

As a quick refresher, ERIS, or energy resource interconnection, means connecting to the grid only to sell energy. If you choose this option, then you aren’t eligible for some of the other network reliability payments, like capacity payments.1 If you want to sell into the capacity markets, you must go through the NRIS, or network resource interconnection service. Network resources are meant to contribute to peak loads and reliability. An energy-only resource is just selling on the competitive wholesale market.

ERCOT is the only market with an energy-only market. However, other grid coordinators claim to have an ERIS process. That ERIS line should be a fast lane. Quicker access to the wholesale market should come in ERIS since there’s no need to verify a plant’s ability to contribute to peak system needs. Unfortunately, the Queued Up 2024 report shows that these ERIS processes aren’t faster than an NRIS process.

The note on the righthand side of the graphic hits a reality policymakers outside of Texas need to face and fix:

The mean [interconnection request to interconnection authorization] duration for ERIS requests submitted since 2010 (33.5 months) is not significantly shorter than that for NRIS requests (~34.2 months) (p = 0.27).

ERCOT, which is not FERC jurisdictional, utilizes a 'connect and manage' approach, similar to ERIS. However, ERCOT requests are processed faster on average (~23.8 months) than ERIS requests in other regions since 2010 (p < 0.001).

To put a fine point on it, even though other states have processes like connect and manage, only Texas gets it right. The explanation here is quite simple. Most generators only planning to sell their electricity are still being put through the NRIS process and judged on deliverability.

Even though other states have processes like connect and manage, only Texas gets it right.

Tyler Norris has pointed out the unnecessary treatment of energy-only applicants as network resources:

…For example, North Carolina and South Carolina’s state jurisdictional interconnection procedures for Duke Energy Carolinas (DEC) and Duke Energy Progress (DEP) require all generators to be studied as NRIS in cluster studies. In both balancing authorities, new solar-only generators are currently assigned minimal capacity value (i.e., effective load carrying capability) unless paired with storage, meaning they are not counted toward resource adequacy requirements. Nevertheless, DEC and DEP still study solar generators under NRIS assumptions for deliverability… In effect, generators without deliverability value are being studied for deliverability, making those generators more likely to trigger network upgrades than if they were studied under more appropriate assumptions. [emphasis added]

Why would energy-only generators be subjected to needless tests and studies? There isn’t much research on this point yet. What exists suggests that the reason for this is simply a way for incumbent generators to bar new competitors from the market. That leaves consumers out and footing the bill in environmental and monetary terms.

What is keeping tomorrow’s solar plants from the grid? Yesterday’s owners of coal, gas, and other sources.

We can pick up an additional reason to think of these extra processes as barriers to competition from understanding how energy-only resources work on the grid. Even though the grid requires a constant balancing act, it’s unnecessary to prevent the addition of new generation to stay online. If there are problems, then the grid operators in Texas can curtail resources as needed to balance the grid.

It won’t surprise you that such a response to keep the grid balanced is possible outside of Texas as well. As engineer and energy markets expert Jacob Mays explains, “reliability concerns need not enter the interconnection study process at all: as long as the relevant constraints for transmission feasibility are included in commitment and dispatch processes, generators could simply be curtailed in real time to prevent violations.”

The Queued Up report hasn’t featured this ERCOT data breakout before. Now that it does, the grid operators for the rest of the country should figure out how to catch up!

Texas can teach you something important if you’re interested in supporting faster deployment of all generation sources.

Andrew Kleit and Todd Aagaard have several studies and a clarifying book demonstrating that capacity markets have an uncertain and tenuous connection to reliability at best. More detailed explanations are scheduled for future entries here, so sign on with Spaceship Earth.