Energy development and agriculture go hand in hand

We should make it easier for farmers to take the next step

“I’ve got a neighbor who won’t talk to me, but her husband will,” Mary Fund told reporters.

The reason for her neighbor’s shunning? Wind turbines on her Kansas ranch and others nearby.

Fund has lived in the area for 45 years, but the land has been in her family since about 1870. Yet the addition of the turbine and the potential wind farm in Nemaha County brought intense feelings about energy development’s place on farmland in Kansas.

Kansas is just one area where the debate is playing out. One in seven counties in the US has some kind of rule against wind or solar development, according to another USA Today report.

On the one hand, the opposition is unsurprising. Solar generation requires putting up fields of panels. A wind farm may enable farming below it, but it adds something to the views and takes some space away from agriculture.

Yet solar and agriculture aren’t really at odds. Instead, what one group would like someone to do with their land is at odds with what they want to do with it. The core issue in debates about whether or not wind or solar farms can replace alfalfa and corn fields is private property rights.

The centrality of property rights is not to say that there aren’t complicating factors. For example, kludgy permitting for transmission processes and building new grid infrastructure to connect solar farms on unused land drives solar development onto farmland that already hosts the needed wires and gear. Remember, it takes three years to build a new transmission line but seven years to do the paperwork to let construction begin.

In this view, transmission lines are the holdup. After accounting for both solar resource quality and transmission availability, farmland looks like the best option. This makes an important point obvious. If transmission lines are really the holdup, then the kinds of NIMBYism inherent in anti-renewables politics will backfire. They introduce additional kludgy processes instead of fixing the root of the problem–that it is too hard to build.

Rather than embracing a zero-sum view that there’s only so much land available for either solar or crops, policymakers should be burning down the regulatory thicket. In practice, this means taking two steps. First, enabling a mixture of farming crops and farming solar by making that permitting process easier at the local level. And second, improving federal permitting rules that slow development by reforming the National Environmental Policy Act. This is particularly important for states with multiple kinds of federal lands. Making it easier to build will open up new areas for our use in farming and energy development.

Heavy-handed energy bans threaten farmers and harm local communities

Discussions of how farmers and ranchers adjust their land usage to include energy production should center on the fact that heavy-handed bans have real costs for farmers. Farmers turn a field of corn into a field of solar panels because they expect to make more from solar energy or want to diversify their incomes. Denying them this opportunity whittles away at their property rights and ownership and robs them of the income that energy development could bring.

Turning to another Kansas farming couple, Donna and Robert Knoche, an elderly ranching couple, have faced immense opposition to adding solar to their crops. As Donna put it in a 2022 hearing, “I never in all my life thought I would stand up here to protect our property rights by being able to use our land legally for the best benefit of our family.”

According to one news report, the Knoches have been trying to add solar power to supplement their ranching since “they were both in their 80s." They are now in their late 90s.

At hearings like the one Donna Knoche spoke at, the objections made to solar or wind are sometimes reasonable concerns that policymakers and landowners should consider. Other times, they are simply incorrect.

Take, for example, worries about property values near installations. Though a common objection is that solar development reduces property values, a December 2024 research paper looking at solar in the midwestern US showed the opposite. Solar adds economic value, not detracts. Combining Zillow data with data on local solar installations, the researchers showed an increase of 0.5-2%. So, it’s not a huge change but a positive one. On reflection, this should be a straightforward realization–solar is an additional use that makes the land more productive by demonstrating a new use.

Some research papers find small property value reductions similar in magnitude to the benefits shown in the 2024 paper. One paper by the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory showed a 1.5% reduction in property value for homes within half a mile of solar developments. However, those effects are small and incredibly local. The researchers found no impact on property values just a mile from a solar installation.

Given the somewhat competing findings, the likely truth is that early solar developments could have done a better job minimizing third-party effects. That’s to be expected in any new industry that is developing best practices. Easy solutions are adding hedges or other natural screens to improve views or placing inverters at the center of solar farms where their noise is unlikely to reach others.

It’s also possible that loud outcries against solar and wind developments can be self-fulfilling prophecies about land values. That would mean that as tempers cool, property values will also return to normal.

Other common concerns are that the development harms the quality of the farmland either by causing erosion and the loss of topsoil, the development of roads on the land, or because of the required equipment’s metals. On the one hand, any kind of development can cause these sorts of tradeoffs. That’s why the United States Department of Agriculture has guidance on how to avoid these problems. On the other, concerns about metals leaching out from panels into the environment do not appear to be common. Where there are real concerns, such as with end-of-life management for solar panels, proper disposal or recycling prevent environmental harms.

In every case, valid concerns are cause for moving forward with best practices, not bans. These delays, permitting costs, and other compliance measures incur real costs. Joshua Rhodes, a professor at UT Austin and consultant with IdeaSmiths, periodically analyzes how much tax revenue and landowner payments are collected in Texas. His work suggests that billions worth of tax revenues and payments to landowners are at stake. Specifically, he estimates that local Texas communities receive around $12.3 billion in additional tax revenues, and landowners receive $15 billion in payments. If people don’t want their neighbors to put up solar, then they should compensate them for the lost opportunity.

Farmers aren’t interested in turning their entire farms into fields of wind and solar

In addition to these forgone opportunities and lost revenues from energy development, many objections to wind and solar development on farmland overlook that few farmers, if any, want to cover every inch of their land in turbines and solar panels. A small survey of farmers and solar developers showed that even though seven out of ten farmers were “open to large-scale solar” on their property, they also wanted to continue raising livestock. That is, they were primarily interested in agrovoltaics–the marriage of farming and solar development.

Notice that half of the responses suggest that the major interest in solar among farmers grows from concerns about paying the bills (supplementary income) and keeping the farm operating or in the family. Simple investment advice is not to put all your eggs in the same basket. For farmers, this is the advantage of adding wind or solar to their crops. They get to diversify their income. If they have a poor crop year, their solar or wind energy can provide some insulation from those downturns. Counties that institute bans on wind and solar foreclose all of these adaptations.

Fundamentally, the choice between crops and energy is really a false dilemma. Some crops and grazing animals may even benefit from the shade provided by panels. With solar grazing, animals eat down the grasses that otherwise require mowing. There are ample places for both farming and energy development.

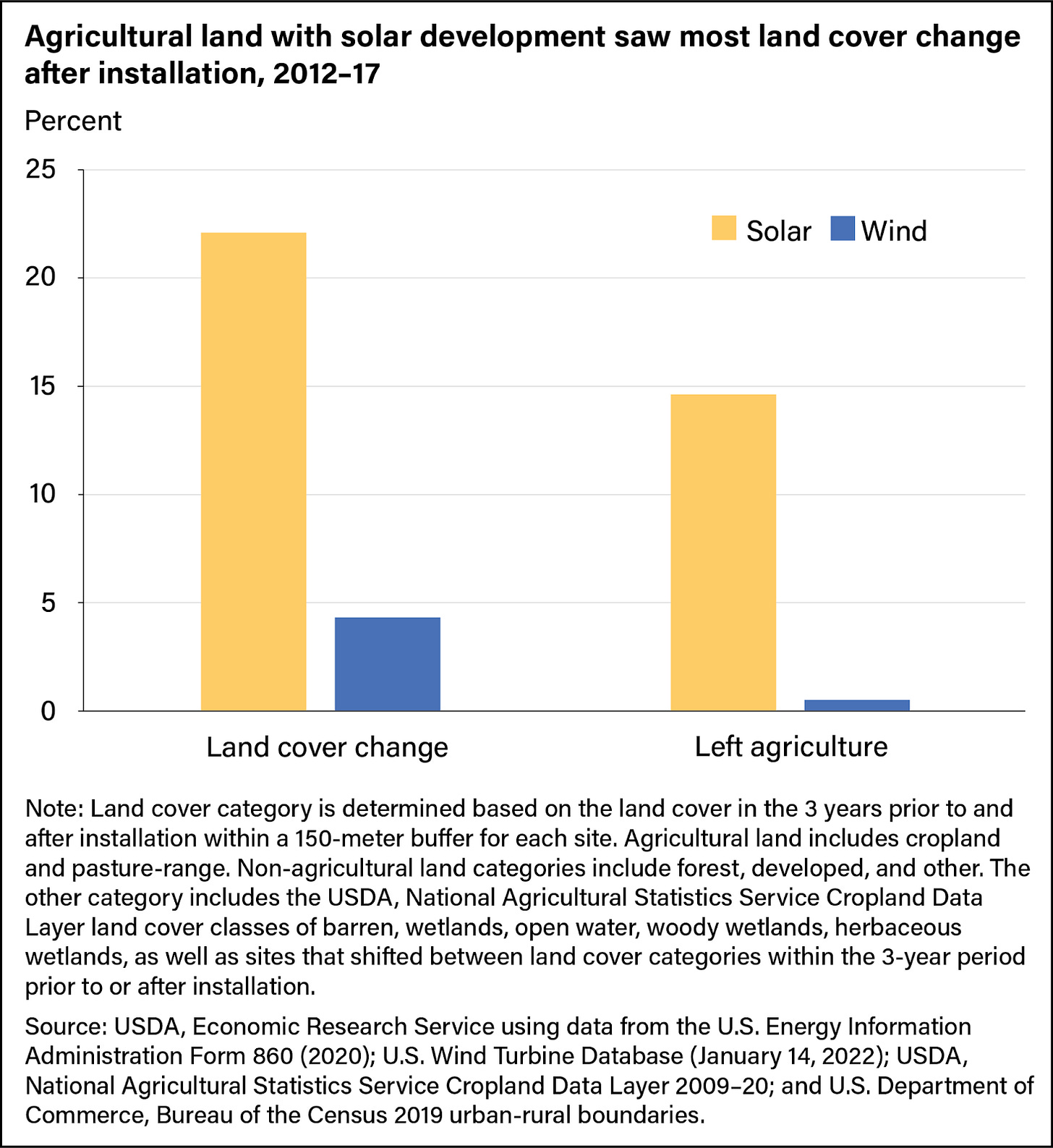

In fact, most of the farmland with new solar and wind development remains in agriculture. The USDA’s Economic Research Service office says that for agricultural land with solar development, only 15 percent left agriculture. In the case of wind, it was only one percent.

Said another way–85% “of crop and pasture-rangeland in proximity to solar farms remained in agricultural production,” according to USDA researchers.

The challenge, however, is that landowners need a hand in clearing today’s thicket of rules and regulations preventing farmers from using their land for both farming crops and farming energy. The same survey mentions that permitting is the main barrier seen by solar developers.

Permits can be costly for landowners. The American Legislative Exchange Council, ALEC, has a great resolution expressing support for community solar and agrovoltaics aimed at county commissioners. State lawmakers or local officials could clarify that agrovoltaics and similar energy development are permitted by right on ranches. Efforts like this are far more promising than bans or heavy-handed siting rules that foreclose on new ways of using farmland.

Fixing the major problem means making it easier to build

Heavy-handed bans on renewable energy projects miss the mark because they don’t aim at the right target. These bans fail to solve the underlying reason that solar and wind often get sited on cultivated fields: it is too difficult to build new transmission lines.

Fixing the real cause of this tension lies in updating and reforming the processes that block or slow new transmission and energy infrastructure on open or less controversial land.

For a place like Utah, where substantial portions of the state are federal lands (and federal lands managed by different agencies), a key problem is the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). NEPA reviews slow projects of all kinds. Transmission projects fall prey alongside geothermal, solar, wind, and pipelines. Federal lands create special delays because projects that touch them require a NEPA review and there are many ways NEPA allows litigation. It can be complicated because a transmission line may cross not just through multiple states, counties, or other local jurisdictions but also through various federal lands, from the Bureau of Land Management to Forest Service or conservation areas like national parks and national monuments.

Of course, it’s not just western states with lots of federal lands that run into this problem. Arnab Datta and James Coleman wrote about the two separate injunctions against the Cardinal-Hickory transmission line that would connect “161 renewable energy projects to the electric grid,” in Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin. Datta and Coleman call this the “litigation doom loop,” an apt name as NEPA reviews and their accompanying litigation encourages project cancellations of all sorts.

The right reforms to NEPA would defang it–limiting opportunistic litigation and adjusting the relevant statute of limitations. President Trump’s first actions around NEPA head in the right direction here. They adjust the implementing rules that agencies use, and he ordered that agencies review their processes for opportunities that will speed up permitting timelines. For what it’s worth, reining in NEPA has been a bipartisan effort–Democratic presidents’s Councils on Environmental Quality also tried to streamline permitting.

That said, NEPA includes no substantive limits on emissions or environmental harms, there’s a reasonable argument that it is entirely unworkable. Reforms here require Congressional action to replace NEPA with substantive environmental protections. This is a tall order but a promising goal. It sets conversations towards the root of the problem by making it easier to build. Reforms here will unlock expansive federal lands for energy development of all types.

When it comes to our permitting regime, policymakers should start from the perspective that the call is coming from inside the house. Our permitting rules cause us to trip over ourselves. Replicating that kludgy process by adding additional permitting requirements to energy development on farmland only entrenches the problem. It leaves us all poorer. Again, the kinds of nimbyism inherent in anti-renewables politics will backfire on growth. They introduce additional kludgy processes instead of fixing the root of the problem.

Policymakers will enrich the world if they choose instead to enable nimble reactions to new energy development. As it turns out, this was a valuable part of previous waves of energy development on US farmland.

Farmland and energy development have always gone hand-in-hand

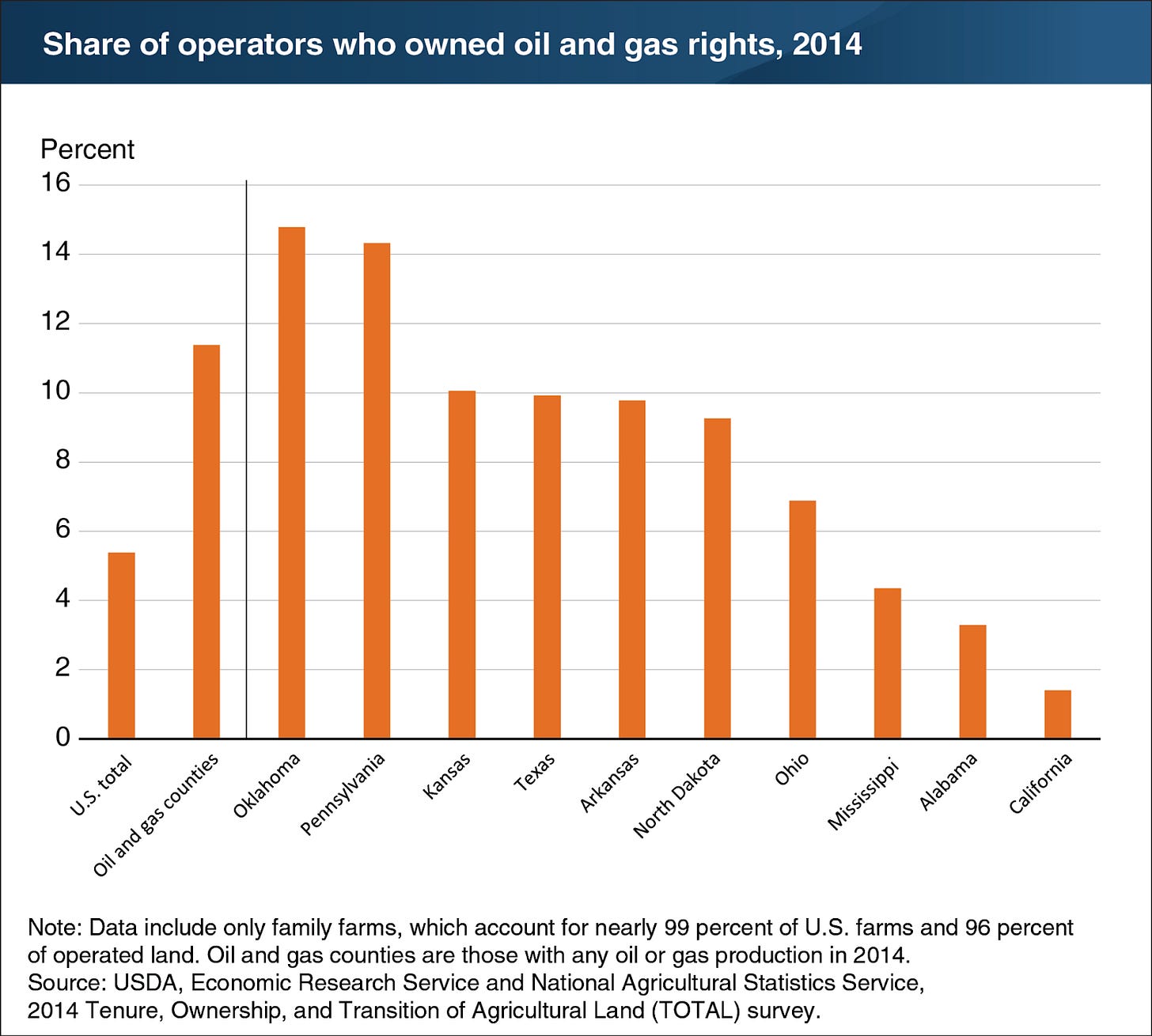

Turning back to the Kansas ranchers for a final lesson–it’s always been the case that farmland and energy development have gone hand-in-hand. Solar and wind are a bit newer around town, but no different from the past. Oil and gas wells have been commonplace on farms for years. Many farmers lease land to oil and gas developers–about one in ten farmers in counties with more oil and gas production.

These statistics underplay the importance of farmland to oil and gas, however. The National Agricultural Law Center says that farmland is where two-thirds of oil and gas production happens in the United States. The USDA says the same. Of the total $338 billion of oil and gas production in the US in 2014, farmland generated two out of three dollars for a total of $225 billion.

Mary Fund is one of those farmers with oil and gas development on her ranch. She noted that she sees wind and solar leases the same way that her mother and aunt saw oil leases. As she told reporters, “They struck oil, so we have a couple of oil wells on our land. They helped my mother in her old age.”

In light of this, solar and wind development on farmland is nothing new. It is simply the next act as farmers and ranchers try to get by.