Proposals to create a set of new requirements for solar developers to wade through pop up in state legislatures each year. One in Utah includes “requirements for lot size, height, setbacks, noise levels, and visual appearance.” However, the need to single out solar rather than apply the same rules to all forms of development is unclear.

In fact, heaping additional red tape and restrictions onto energy developers gets the problem backward. The fundamental problem plaguing energy policy is an inability to build.

The core risk with these proposals is that they will go too far. Take, for example, the noise level and decibel requirements. The role and purpose of noise controls on development or land uses are not in serious dispute. Anyone with a loud neighbor understands this problem. Yet, a limit of 40 decibels (dB) is a strange element to include. Solar farms simply don’t create much noise pollution anyway. Research overwhelmingly points out solar farms are quiet.

On the one hand, solar farms will easily pass such requirements. However, this misses the regulatory thicket created by unnecessary rules. Each branch and thorn in the thicket requires additional work to avoid. In turn, investments become less attractive.

Of course, it’s even worse than this implies. The regulatory thicket is also used offensively wielded against property owners and project developers. Red tape creates a set of levers and buttons that enable protests and raise the costs of any project. Unnecessary noise controls are best thought of as exactly this–buttons and levers to push and pull that prevent change. They represent red tape eroding the property rights of landowners.

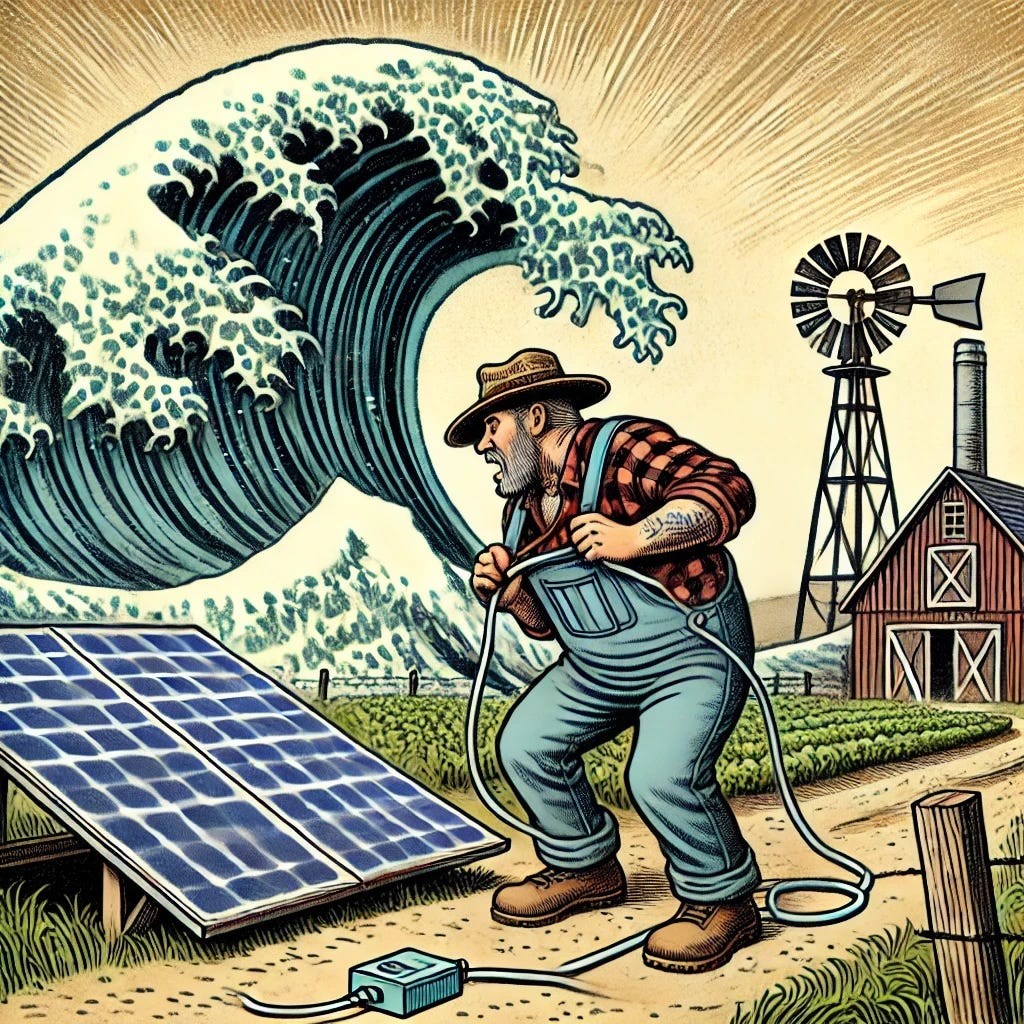

The big takeaway is this: If we're going to bicker about how many feet a solar farm can be from a forest, how many decibels it can register at, or if a farmer can add solar to his crops, then we'll never do anything great.

Solar siting problems are nothing compared to siting for nuclear waste, nuclear plants, or other energy siting like pipelines. The imagined problems of solar developments will justify obstructionism preventing not only solar but nuclear, pipelines, mining, and everything else. The logic of such protests against solar extend to and so endanger all energy projects. They are Down Wing arguments, to borrow from James Pethokoukis’ book, The Conservative Futurist.

States that want to attract investment from industry, reindustrialize America, or simply green their energy supply should focus on burning down the regulatory thicket in our way. The conversations about meeting the electricity demands of industry, technology companies building new data centers, and keeping the lights on for all of us come back to a simple problem–we have made building energy generation of all types difficult or impossible. It’s a crisis of our own making.

Reforms should be streamlining permitting for all energy sources. Doing this right means setting rules that allow property owners to make responsible decisions about using their land, not arming anti-energy protestors.

Energy development is increasingly under threat from the regulatory thicket

About one in seven counties in the US have, according to a USA Today investigation, “effectively halted new utility-scale wind, solar, or both.” Research from the Abundance Institute shows the same trend–an increasing number of local permitting blockades set up against energy development.

These policies only frustrate energy development and energy use. And though the above graphic measures anti-wind and anti-solar policies, they extend far beyond just those technologies. New natural gas connections, for example, have been outlawed by some 70 jurisdictions across the country. Other organizations publish model code to prohibit fossil fuel infrastructure of all kinds.

These kinds of bans, no matter the target, wall off large parts of cities, counties, and states from opportunities to develop energy resources. Individual elements motivating these kinds of bans may sound reasonable in isolation. Yet, they are part of the red tape that strangles economic growth. Looking under the hood at the noise requirement for solar farms is a revealing example.

How loud is too loud? 40 decibels is like a quiet library

The right starting question is, how loud is too loud? Many cities set their noise ordinances by simply saying that you shouldn’t be able to hear neighbors during quiet hours. Of course, the difficulty is that certain uses cause noise. For example, a substation and its equipment can make noise ranging from 20 dB to 80 dB.

The limits in Utah’s proposal vary —the quietest requirement is 35 dB for areas bordering residentially zoned lands during quiet hours. The graphic below from an environmental consulting company illustrates a range of familiar sounds. The 35-decibel requirement effectively establishes whisper-quiet rules. The American Academy of Audiology suggests that 40 decibels is about the noise level of a quiet library.

Think about what the units mean here. A 10 dB increase is considered a doubling in noise. Notably, a refrigerator is louder than the limit set in the proposal. To give you another reference point, 40 decibels is 8 times quieter than a car driving by (70 decibels). This is because each increase of 10 decibels is about a doubling of the noise. So, with a difference of 30 decibels, the noise level of 40 decibels is 23, or 8 times quieter than 70 decibels.

Now, apply that unit understanding to the noise requirement at hand. The problem here is that if a landowner wants to build a solar farm, it can only make an eighth of the noise that a car does. This puts a potential solar farm at the mercy of almost any objection, even those more imagined than real. That is, it is more like the neighbor who calls the city to complain that your trash cans are still out the day after trash pickup than the neighbor inconvenienced by your use of property.

People will always have opinions on change

The reason proposals to arm NIMBYs against solar are popping up often connect with solar farms with farmland. In Georgia, for example, one Brooks County resident said, “Some of the best farmland [in the state] is here is in Brooks County. And if we use this up for panels, solar panels, if all this farmland is taken in, what are we going to have?”

Change always engenders some pushback. Take a funny example from Logan, Utah’s Saddleback Mountain trail. In 1967, the Mountain States Telephone and Telegraph Company installed reflectors that sent radio and telephone signals. As technology evolved, the reflectors sat unused on the mountainside of Cache Valley for decades.

In 2022, 55 years later, they were taken down. One resident’s reaction, as quoted in Utah Public Radio:

It's terrible. It's kind of like a landmark because whenever we're talking about mountains down in the valley, and you say, check out Saddleback Mountain. Well, where’s Saddleback? You can always tell them, it's where the billboard reflectors are.

This sentiment stems from a wonderful human attribute: We care. In this case, we care about the equipment once owned by a radio and telegraph company that has looked down on the valley for as long as we can remember.

Yet this caring can mislead if it’s our only guide. The reflectors are trash to one and treasure to another of Cache Valley’s residents. It’s entirely human and normal for people who see acres of farmland become acres of solar (or homes, or strip malls, or anything else) to miss what used to be.

With these conflicting visions in mind, there’s little reason to give either side a veto over the other’s choices. Instead, policy could allow people opportunities to put their money where their mouth is on these disagreements. If you don’t want your neighbor’s farmland to change, then you could pay him to leave it fallow rather than plant solar panels. You could band together with a group of neighbors, purchase the development rights, and then sell those rights to others so that already developed areas can get denser. As for the acres you now own in common, you could turn it into a park or continue grazing it or farming it, depending on your common goals.

A tidy bonus of such bargaining, rather than government intervention, is that it reflects the real costs involved. In either outcome, the “losing” side is compensated. Wanting to stop something you don’t like is natural, but it isn’t free. Institutions that let people solve their problems this way gives politicians a way to cut through the complaints with merits and the complaints that reflect, instead, nothing but NIMBYism.

Such an approach may sound unorthodox or unworkable, but that is only because we have become accustomed to giving into the complainers. Nobel laureate Ronald Coase originated the academic theory of these solutions, known as Coasian bargaining. The Property Environment Research Center in Montana uses this thinking in its policy work. One example, setting up agreements to reimburse ranchers for the cattle killed by wolves so that ranchers stop opposing the reintroduction of wolves.

The difference between these mutually beneficial solutions and today’s deference to NIMBYism is that everyone can win.

More policies should include a filter that requires a financial stake from those who oppose a change. The zoning restrictions, land use regulations, and noise restrictions in many anti-solar bills fail this test. They let complainers cheap-talk their way into getting their way at the expense of the farmer looking to add solar to his crops. Heavy-handed rules thereby whittle away someone’s property rights without just compensation.

Deal directly with real harms, but don’t arm the NIMBYs

The role and purpose of noise controls on development or land uses is not in serious dispute anywhere. However, the layering of noise, distance, and use restrictions onto property owners without clear evidence of harm is questionable. The real noise problem is cheap talk.

Ultimately, this slows the natural evolution of any town, city, or resource, preferring to seal the area in amber instead. This kind of freeze is the wrong approach if Utah wants to lead in energy innovation. Reforms should be breaking down barriers to entry of energy entrepreneurs of all kinds.

We’ll need to sympathize with folks that are inconvenienced, of course. But we can’t let those inconveniences keep us stagnant. Public service obligates legislators and public officials to listen to opposition and complaints. Yet they need not hand complainers weapons to bludgeon others.

Policymakers should focus on real impacts and allow landowners to adapt as opportunities arise. A vibrant energy future means welcoming adaptation and innovation, not entangling them in needless regulations.