Shout it from the balconies

A European innovation the US fumbled in 2011

What if you could just plug solar panels in like an appliance? Instead of pulling power through your outlet from the grid like a stove or lamp, it would push power through the outlet to the grid.

This is the reality of plug-in solar in Germany. You hang the panels on a porch or balcony and plug them into an outlet. Watching how-to videos for these is like watching a video from Ikea.

Because they're often installed on apartment balconies, they’ve earned the nickname “balcony solar.” Over 400,000 of these systems are registered with the German government. Why so many in Germany? German regulators pursued a permissionless environment around these balcony solar panels. The installation and registration are simple.

Regulators in the US should make the same possible for the US. It turns out that the US Department of Energy’s Sunshot Initiative discounted the idea of plug-in solar back in 2011.

Why not rooftop solar?

For many, the rooftop solar installation costs simply don’t make sense. Renters are unlikely to capture the value of a residential solar system. But anyone who is thinking about moving is in a similar position. For years, we’ve known that it’s mostly wealthier households who can afford the upfront costs of solar. Balcony solar is a fit for many of these groups.

The systems are simple and small–limited to 800W. This is about the same as many everyday appliances consume, often less. A microwave, toaster, hair dryer, and certainly a space heater are drawing about this much power or more when flipped on. Space heaters are likely drawing 1,500 watts, and so is your hair dryer.

The big picture is that plug-in solar systems emphasize ease. This gives them a big advantage over rooftop solar installations. A central problem for rooftop solar is installations take a long time. Permitting and inspections are required before your rooftop panels can flip on to power your home or feed electricity back onto the grid. Trained workers are sometimes in short supply as well.

None of this is needed with plug-in solar. Given their size, balcony solar systems are more likely to offset some consumption rather than take you off-grid. Unless you connect them to batteries and use only a bare minimum of electricity, they’re just reducing your draw from the rest of the electrical grid. This is why they’re so easy and how Germany has installed nearly half a million in the last six years.

How Germany set balcony solar free

Several factors lay behind the popularity of balcony solar systems in Germany. First, German electricity prices trend high, so some of their popularity likely reflects that incentive. Another reason for their emergence is the steep decline in costs of solar panels.

The key reason for plug-in solar’s success is their permissionless treatment. The German focus has been on rolling these systems out within reasonable limits. The process is as simple as plug-in solar implies. You buy a system, take it home, hang the panels, plug the panels into the inverter, and the inverter into your outlet. You’re generating as soon as you’re plugged in. Then you register your system.

The systems are small, representing a tiny fraction of German electricity generation. They are even a small part of only solar generation and capacity. But the installations are climbing. A report by a German research organization shows the growth of solar installations of all types since 2018. Balcony (balkon) and small generators are only a small fraction. As you can see, they’ve grown from unnoticeable to just barely noticeable.

Based on a recent suggestion from a German electrical engineering association, the registration process has been made easier. The registration system requires a few questions about the module and is done entirely online. These are simple questions–the number of modules, the power of the modules, the inverter’s type and sizing, and if it’s connected to a battery storage system. It is like filling out a warranty form or a registration for an appliance.

You can walk through the registration process online if you make an account. You’ll notice that these are all questions about what you are doing, not requests for permission to install them. One of the questions is about whether you are already generating or not. That’s an enviable approach–a perfect encapsulation of the potential of permissionless design.

If you think a room heater is ok, then you should think that plugging in a solar panel is ok

Most people don’t consider the relative power usage or the actual wiring of their system at home. This confusion about the safety of the system is likely to be a barrier to the adoption of balcony solar in the US. As always, you should talk with an electrician if you want to evaluate the ways plug-in solar would affect your home.

To get a handle on how these systems work, think about balcony solar like a space heater. You can go to the store and buy all the space heaters you want. No one can stop you. Generating small amounts, like plug-in solar, should be a similar story. There’s no reason that the system cannot work in reverse.

To be clear, it’s not that there are no risks from plug-in solar. There are risks to your space heaters, after all. The National Fire Protection Association notes almost 15,000 home fires caused by heating equipment like space heaters each year from 2016-2020. In fact, space heaters are “most often responsible for home heating equipment fires,” according to the Association. Instead, the risks of balcony solar are small and manageable. Existing technologies already provide solutions.

The major concern is backfeeding from your home to the wires outside. This is a public safety issue because a utility lineworker may come to work on the lines and find them energized when they believe they are off, which can electrocute a lineworker. To fix this issue, plug-in solar systems feed their power into an inverter. The inverter’s primary role is matching the direct current (DC) to the alternating current (AC) that your home uses. But it also monitors the house’s consumption and turns off if it senses that the home is no longer pulling from the electrical grid. A 2016 review by three electrical engineers found that common inverters could already provide this function.

Those engineers also identified some likely barriers to the emergence of balcony solar in the US. A primary one is that applying the same permitting and other requirements to plug-in solar would smother the industry. For small, ~1 kW systems, such rules are simply unnecessary.

Rooftop solar faces high installation barriers but provides much more generation. Working through the red tape of permitting and connecting to the utility can still make financial sense. However, balcony solar doesn’t need such requirements because the systems are small and unobtrusive. You need a building permit for installing rooftop solar, but you don’t need that for plug-in solar. Installing plug-in solar is “functionally equivalent to installing a beach umbrella,” the engineers write.

The US missed an opportunity on balcony solar

Germany is the right case study for international peers to follow. It’s not that the US and other places don’t have any plug-in solar. A few companies are providing the same kind of systems. An older company is Plugged Solar, which has sold panels to customers in at least 35 states. Instead, the US has created regulatory roadblocks that Germany has removed.

I called Plugged Solar and asked them about their panels and the system. They told me they initially had a lot of trouble from regulators. But because they use UL 1741-certified pieces, the pressure relented. The inverter automatically stops panels from generating when the grid is down, so there’s no risk of backfeeding and harming lineworkers.

As Plugged Solar confirmed with me on the phone, the analogy policymakers (and potential customers) should think about is with space heaters. Your heater is a big electricity draw. The plug-in solar installations are simply this in reverse. You bought an air fryer without concern and without permission–it likely is rated around 1800W. That’s twice the size of German plug-in solar systems and more than double the 750W plug-and-play solar option from Plugged Solar.

Another example is the YouTuber Everyday Solar. In February, he posted two videos about simply plugging in solar panels via an inverter. His videos suggest a similar experience–the officials that he talked with said that they’d approve it as long as it does not backfeed when the grid is down.

What seems to be crystal clear is that the US could have plug-in solar in a much bigger way. There are some early signals that plug-in solar was one avenue that the industry and public officials were traveling. In fact, Plugged Solar highlights a line and framing from the Department of Energy’s Sunshot Initiative back in 2012, “In the future, installing a solar array for your home could be as easy as plugging in common household appliances, which are purchased, installed and operational in one day.”

These challenges reflect a failure of imagination. The Department of Energy’s 2021 Solar Futures Study doesn’t envision simply plugging in small generating panels. Conference meeting notes from a 2011 Department of Energy Sunshot meeting say, “Standard home wiring today cannot handle a 5 kW PV system plugged into an existing outlet.” But what about an 800W system? One that is about half the strength of your hair dryer?

Yet, 12 years later, the confusion about plug-in solar abounds. Reports from industry websites suggest that it is against the rules of many jurisdictions. GismoPower is another company in this space. They sell larger installations on wheeled carports that then plug in with 240V outlets (what your dryer might use).

GismoPower’s market is charging electric vehicles. However, the company has landed in regulatory limbo. The regulators told them, “I have neither approved nor denied permit 21-177673 00 BI for your interconnection of a portable grid-tied solar EV charger appliance.” The company is now working with other plug-in PV companies to come up with solutions.

Looking at the last decade of efforts by Sunshot, it looks like it chased down permitting problems for rooftop solar and tried to simplify those rules. The “plug-and-play” use that they emphasized from 2011 ended up as not “plug-in” solar, so much as, “How do we simplify permitting for rooftop solar?” Sunshot is also a large program that has many irons in the fire. Plug-in solar was dismissed early and has remained forgotten.

An easier time on the balcony

Given the rollout in Germany, it’s time for policymakers in the US to make room for balcony solar and other plug-in solar options. For the most part, the existing rules and regulations are sufficient. Plug-in solar equipment should undergo the same UL 1741 certification as other electronics. Inverters are necessary not just for the DC to AC switch but also to prevent backfeeding. People interested in trying plug-in solar should keep systems small, around 1 kW, and be cautious, just like they are with space heaters.

The real barrier is that most jurisdictions will likely try to apply rooftop rules to balconies. This is misplaced and implies a regulatory burden much too high for the relevant risks. Mitigating risks is straightforward with existing technology.

In their study, the electrical engineers suggest some simple precautions that policymakers could consider if they must have special rules. One is having plug-in solar use a dedicated outlet external to the home. These outlets tend to be used less and so are some of the least likely to be overloaded. Adding such an outlet is an additional cost that varies by location but could be about $250 or so. Of course, because plug-in solar products cost just ~$1,000, this is a substantial increase in price.

A simple registration system isn’t out of place either. The German system is the right example to imitate. The system should simply be a notification that you are installing one, not a request for permission.

The US should make this same kind of permissionless world possible. Larger rooftop installations will never make sense for many Americans. But balcony solar could have a place just as it has in Germany. That could be because you want to cut your power bill, or it could be that you want to reduce your pull from the utility, or it could be an environmental goal.

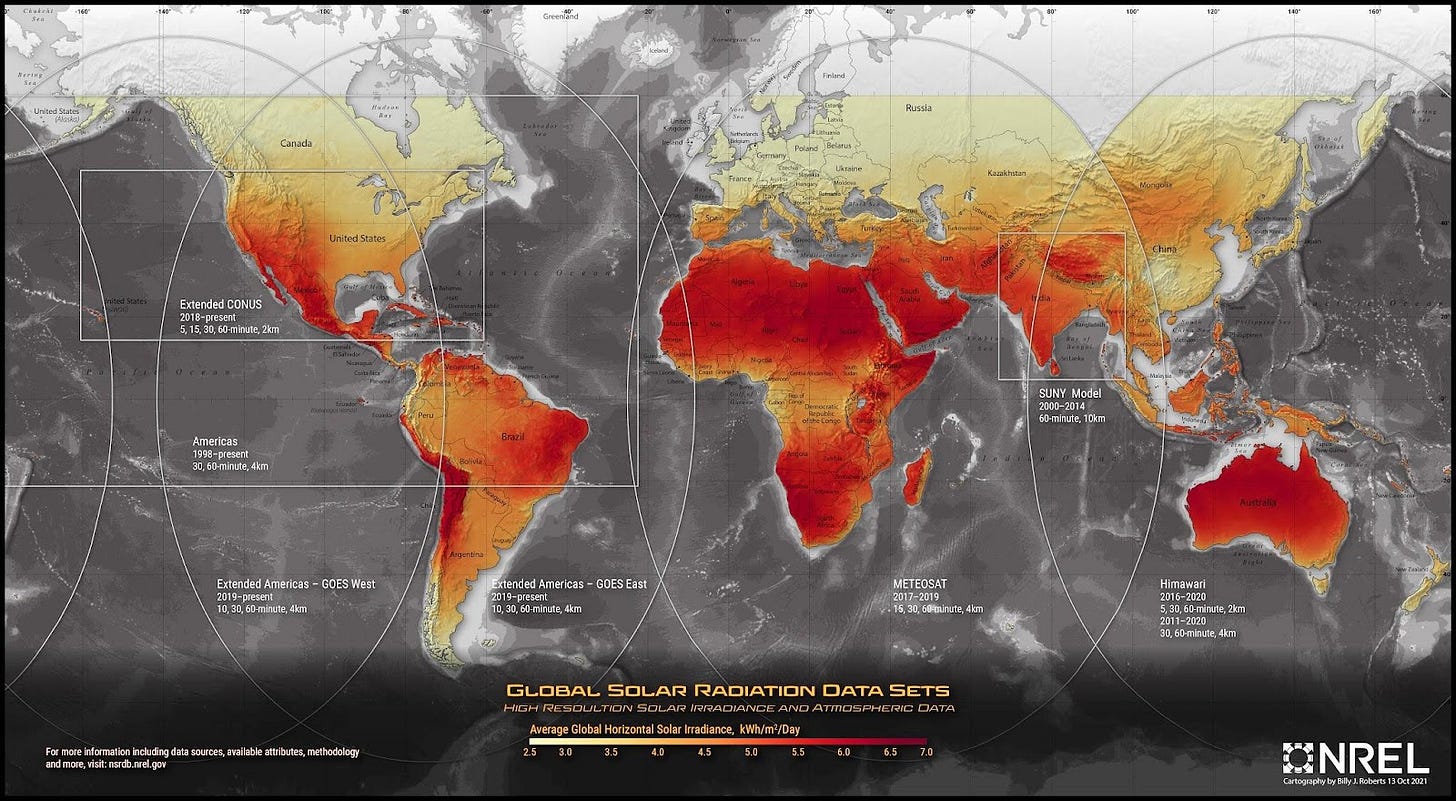

Most of the US has better potential for solar generation than Germany. We simply need to let these systems grow. Where possible, regulators should be clarifying that the systems are allowed and removing unnecessary rules around them.