Connecticut Yankee: 5 years and $1 billion

Again, the call is coming from inside the house

Samuel Florman was an engineer and author. Reading his Blaming Technology collection of essays, I found this excerpt on nuclear mindblowing. Connecticut Yankee was built in about five years and for about a billion in current dollars.

Here’s how Florman tells the story:

…I thought of how, just a few years earlier, nuclear power was considered to be a dream come true: a clean, cheap, compact source of energy that would carry our civilization to new levels of sparkling achievement.

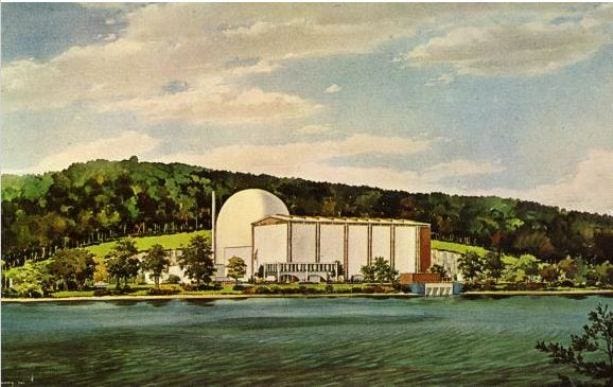

In December 1962, a group of New England utility companies formed the Connecticut Yankee Atomic Power Company and planned to build a nuclear plant at Haddam. A mood of buoyant anticipation prevailed. There were no "intervenors" to challenge the project with extended lawsuits, no Clamshell Alliance to stage demonstrations on the proposed site. Ralph Nader was an unknown lawyer just about to take up the cause of automobile safety.

In mid-1963, the Atomic Energy Commission approved an application for the construction of the new facility, which was then designed, reviewed, and built at a pace we can only marvel at today. When commercial operation began on January 1, 1968, just five years had elapsed from the time of the initial application to the AEC. The total cost of the project amounted to a little more than $100 million.

By the time of my visit, the lead time for building a nuclear plant had grown to ten to twelve years, and the cost was approaching $2 billion…

Contrast Connecticut Yankee with the experience of the recent Vogtle reactors in Georgia. They started construction in 2009, were expected to be completed in 2016, but actually came online in 2023 and 2024. That’s 14 years of only construction–we’re leaving out the process Florman mentions of permitting, licensing, and the other work that companies do before pursuing a project.

In short, it took 14 years to build, additional time for the paperwork, and then an estimated cost of “more than $30 billion.”

You can also see Florman’s experience in the EIA’s chart of nuclear power capacity additions from 1960 to 2024.

What’s on display in the EIA’s illustration of the last 50 years is an industry strangled by red tape. Regulations multiplied, timelines stretched, and costs spiraled out of control. This happened not because the technology was flawed but because the rules strangled progress.

The call is coming from inside the house.

The only point to quibble on in Florman’s analysis is that we can do more than marvel at the pace we set in 1962. If we’re right that the problem is a combination of vetocracy and red tape, cutting back those thickets can create the world Florman imagined 62 years ago.

Florman closes his book with a compelling case for why we should make building easier:

For all our apprehensions, we have no choice but to press ahead. We must do so, first, in the name of compassion. By turning our backs on technological change, we would be expressing our satisfaction with current world levels of hunger, disease, and privation. Further, we must press ahead in the name of the human adventure. Without experimentation and change, our existence would be a dull business. We simply cannot stop while there are masses to feed and diseases to conquer, seas to explore, and heavens to survey.

Press ahead!

New video: The case for nuclear power

Taylor Barkley stars in our new video about the case for nuclear power. Check it out!

The call is coming from inside the house

Problems that will splash across the evening news tonight are almost all downstream of an inability to build. They cut remarkably across the usual partisan lines: